Precautions When Quoting from the Copyrighted Works of Third Parties for e-Learning Content

Use of the Copyrighted Works of Third Parties for e-Learning Content

Please refer to the following handouts provided at the Engineering FD Workshop held on October 30, 2012.

Use of the Copyrighted Works of Third Parties for e-Learning Content

– Principles and legal underpinnings, experiences and advice of the Open University of Japan, and HU’s proposals for improvement –

1. Principles of using third-party works and legal underpinnings for use without seeking permission

Principles: The use of third-party works requires permission from the copyright holders (e.g., authors, publishing companies).

Legal underpinnings for using such works without seeking permission:

(Clear indication of source) Article 48 of the Copyright Act: In each of the cases listed in the items below, the source of the work as provided for in such item must be clearly indicated in the manner and to the extent deemed reasonable in light of the manner of the reproduction and/or exploitation:

(i) where reproduction of works is made pursuant to the provisions of Article 32, …

2. Advice from Prof. Shiro Ozaki of the Open University of Japan, and judicial precedents

Since law is abstract, CEED sought advice from the Open University of Japan from a viewpoint of investigation into judicial precedents.

A. 1 I’ve looked for them, but haven’t found any.

Q. 2 There are precautions to take when we quote from third-party works in our research papers. Do the precautions also apply to e-learning content?

A. 2 I couldn’t find any relevant judicial precedents, but if legal action is taken for the following two cases, they are considered to give different impressions to the judge. (The judge will probably rule that 2) is against the law.)

1) Third-party works are quoted only partially in several pages of a research paper.

2) Third-party works are quoted in the whole of a Power Point sheet as e-learning content.

Q. 3 Why is there no judicial precedent concerning e-learning content?

A. 3 This is because the nature of e-learning being not for profit makes it easy to reach a settlement when a complaint is filed by the copyright holder. The use of e-learning content in relatively small groups in a closed setting is also considered as a contributing factor.

Q. 4 What are the fees when you ask to use third-party works for e-learning content?

A. 4 I heard that a university asked about 100 copyright holders to authorize the use of their works, and that most of them agreed without any charge. I also heard that only several of them charged fees, which amounted to approximately 200,000 yen to 300,000 yen in total. Some copyright holders highlight not monetary but emotional issues, with one copyright holder replying that if the university uses photos of his temple, he wants the university not to use those taken by Company XX. In regard to such fees, there is no standard rate, and the amount is determined by the will of the copyright holders.

Q. 5 Are there any other considerations to make?

A. 5 It’s believed that there is no problem as long as we pay as much attention to quotations as we do when writing books (e.g., textbooks).

Judicial precedents concerning copyrightability: The court rulings below show that not all materials are copyrightable works. The important numbers shown are the same as those in the handout provided at the 2012 Educational Copyright Seminar held at HU on September 4, 2012.

2) A case holding that interview material based on actual facts is copyrightable if the author’s originality is displayed in his or her choice of words or expressions (Tokyo District Court judgment of October 29, 1998, on the SMAP Interview Article case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1658, p. 166))

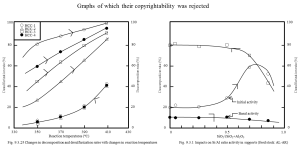

5) A case ruling that graphs as mere representations of data using an ordinary method are not copyrightable (Intellectual Property High Court judgment of May 25, 2005, on the Kyoto University Doctoral Dissertation case (the Court’s website))

7) A case holding that the resolution process for propositions in mathematics is a thought itself and is therefore excluded from copyright protection (Osaka High Court judgment of February 25, 1994, on the Nogawa Group case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1500, p. 180))

9) A case holding that objective facts, procedures, methods and ideas per se are excluded from copyright protection (Tokyo High Court judgment of September 27, 2001, on the Kaibo jisshu no tebiki (Anatomy: a guide to laboratory technique) case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1774, p. 123))

13) A case ruling that architectural works refer to buildings of great artistry (Osaka District Court judgment of October 30, 2003, on the Model House case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1861, p. 111))

15) A case holding that originality is rejected when program descriptions are mundane (Tokyo District Court judgment of January 31, 2003, on the Drafting Program case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1820, p. 127))

3. Summary of this document

- In principle, when you use the works of third parties, you must get permissions from the copyright holders.

- When quoting from third-party works, you can consult judicial precedents that rejected copyrightability.

- When you quote from third-party works for e-learning content, you are expected to pay as much attention as you do when writing textbooks and other books.

Note: The term “quote” in this document means using third-party works without seeking permission within the scope of Article 32 of the Copyright Act.

4. Topics for discussions for improvement and information on CEED activity

4.1 Improvement of the environment to ensure that the teaching staff can produce e-learning content without worry of possible copyright infringement.

Proposal 1: Consideration of the possible appointment of a lawyer in case of copyright infringement

Proposal 2: Activities to spread the internal regulations on e-learning across HU

4.2 Establishment of a long-term e-learning content plan for each division

Goal: Eight courses per division

Reasons: The credits to be earned from those e-learning courses correspond to 16 credits to be earned from major subjects at a graduate school, and students can take e-learning courses intensively before starting their long-term overseas internships.

4.3 CEED videotapes lectures offered in English and broadcasts the videos as e-learning content to the university’s overseas partner institutions. Cooperation with the videotaping of such lectures is highly appreciated.

Contact: CEED e-Learning Initiatives: ceed-eL◆eng.hokudai.ac.jp

*Replace ◆ with an at sign.

October 30, 2012, Junichi Shinohara at CEED is responsible for the content of this document.

Judicial Precedents Concerning Copyrights (Reference)

I. Judicial precedents concerning copyrightability

1) Case of rejection of the copyrightability of data (Nagoya District Court judgment of October 18, 2000, on the Automotive Parts Manufacture and Distribution Survey case (Hanrei Times, No. 1107, p. 293))

It is clear that the data in question are a summary of …, and each piece of data constituting a summary are objective facts or events and do not express thoughts or sentiments. … The data per se do not receive copyright protection, even if large amounts of cost, time and labor have been spent to collect them.

2) Case holding that interview material based on actual facts is copyrightable if the author’s originality is displayed in his or her choice of words or expressions (Tokyo District Court judgment of October 29, 1998, on the SMAP Interview Article case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1658, p. 166))

Originality does not require ingeniousness or novelty in expression, and it is sufficient if the author’s individuality is apparent in the way in which the thoughts or sentiments are expressed. Therefore, even if the article is based on objective facts, it can be considered copyrightable if the author’s originality is recognized in the selection and arrangement of the material in the article and written expressions, that is, the choice of words and the word order, and if the author’s thoughts or sentiments are expressed in the form of evaluation, critique, etc.

3) Case ruling that it is sufficient if the author’s individuality is visible in the tangible expression of thoughts or sentiments (Tokyo High Court judgment of February 19, 1987, on the Election Tip Sheet case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1225, p. 111))

It is appropriate to consider that thoughts or sentiments indicate overall human mental activities, that expressed in a creative way does not demand ingeniousness in the strict sense or the absence of similar examples, that it is sufficient if the author’s individuality is visible in the tangible expression of thoughts or sentiments in some form, and that falls within the literary, scientific, artistic, or musical domain indicates the overall products of intellectual and cultural mental activities.

4) Case ruling that news article headlines have relatively little room to display the authors’ originality (Intellectual Property High Court judgment of October 6, 2005, on the Yomiuri Online case (Court’s website))

Generally speaking, article headlines in news coverage have restrictions such as character limits and the need to be succinct and accurate in conveying the main points of the articles to readers. Accordingly, it is difficult to say that the headlines offer a broad range of options for expressions, it is undeniable that they have relatively little room to display the authors’ originality, and affirming their copyrightability is thus not necessarily considered easy. However, it should not be hastily concluded that all article headlines in news coverage fall under Article 10, Paragraph 2 of the Copyright Act and that it is thus rejected that they are copyrightable. Rather, originality may be affirmed in some headlines depending on the used expressions. In the final analysis, expressions used in each article headline should be examined to decide whether they are original or not.

Note: In this case, all 365 article headlines were rejected as being copyrightable, with the court ruling that they did not contain sufficient original expressions.

5) Case ruling that graphs as mere representation of data using an ordinary method are not copyrightable (Intellectual Property High Court judgment of May 25, 2005, on the Kyoto University Doctoral Dissertation case (the Court’s website))

In graph representations of data (such as experimental data), the data can be expressed in various graphical forms, such as polygonal line graphs, curved line graphs and bar graphs with scale setting options and the possibility of partial data omission. However, since data per se, such as experimental data, are facts or ideas and therefore do not constitute works, the mere representations in graph form of such data using an ordinary method should be considered to lack the originality necessary to be copyrightable, even if they have a certain range of expression.

6) Case holding that the laws of natural science and their discovery and related technical ideas are excluded from copyright protection (Osaka District Court judgment of September 25, 1979 on the Light Emitting Diode Paper case (Hanrei Times, No. 397, p. 152))

The Copyright Act protects, as works, the form of original expressions of thoughts or sentiments that are tangibly manifested in words, letters, sound, color, etc. The content thereof, namely, thoughts or sentiments per se, such as ideas or theories, except novel stories, etc., principally cannot be works, even if they have ingeniousness and novelty, and they should be considered to be excluded from protection under the moral rights of author or copyright prescribed in the Copyright Act (the so-called principle of free circulation of ideas). Especially since the laws of natural science, their discovery and the inventions that are the creation of technical thoughts based on the laws are common facts for everyone, and anyone should be allowed to use them freely, it should be considered that they cannot be protected under the moral rights of author or copyright prescribed in the Copyright Act, and that the inventions could merely be protected under industrial property rights, such as patent rights, utility model rights and design rights, not under the moral rights of author or copyright. However, in regard to the laws of natural science, their discovery and any inventions using the laws, it should be considered that if there is originality in the ways they are described and if the original expressions of the logical process, etc. fall within the scientific, artistic or other domain, then separately from the content, the said form of expressions could be protected as a work under the moral rights of author or copyright.

7) Case holding that the resolution process for propositions in mathematics is a thought itself and is therefore excluded from copyright protection (Osaka High Court judgment of February 25, 1994, on the Nogawa Group case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1500, p. 180))

It is appropriate to consider that the copyright holder for a work relating to mathematics cannot receive copyright protection for the resolution process for propositions presented in the work and equations used to explain the propositions. Generally speaking, the purpose of publication of science is to communicate to the public useful knowledge that it contains and to give other scholars, etc. opportunities to further develop that knowledge. If such development constituted a copyright infringement, the purpose of publication cannot be achieved. In mathematics also, which belongs to the academic field of science, it would be impossible to work based on the premise of the resolution process for propositions, including the development of the equations used to explain the propositions, to further develop the same. The process is considered to be the thoughts (ideas) of the work per se and does not fall within the category of works as provided in the Copyright Act, although rights may be asserted under the Copyright Act if originality is recognized in the form in which the resolution process for propositions is expressed.

8) Case ruling that theories or thoughts per se are excluded from copyright protection (Tokyo District Court judgment of April 23, 1984, on the Nihon no meicho Miura Baien (Japanese classics – Miura Baien) case (Hanrei Times, No. 536, p. 440))

Although the plaintiff argues that … the descriptions in the defendant’s book … were plagiarized from the plaintiff’s theories or thoughts expressed in the descriptions in the plaintiff’s work and that it constitutes an infringement of the plaintiff’s copyright, it goes without saying that theories or thoughts per se do not fall within the ambit of protection under the Copyright Act, and the plaintiff’s argument itself should therefore be considered improper.

9) Case holding that objective facts, procedures, methods and ideas per se are excluded from copyright protection (Tokyo High Court judgment of September 27, 2001, on the Kaibo jisshu no tebiki (Anatomy: a guide to laboratory techniques) case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1774, p. 123))

It goes without saying that objective facts, such as the structures of human organs and the relative positions of the organs, arteries, veins and nerve plexuses, and dissection methods and procedures, as contained in the publication at issue as well as ideas concerning the same in themselves, should be freely available to the public and should not be exclusive to certain people. Accordingly, in regard to the publication at issue, which is a laboratory training manual, things that can be regarded as originality of expression as the basis for copyright protection under the Copyright Act should not be the originality of the objective facts, methods/procedures or ideas expressed, but should be limited to the originality in expression that can be recognized based on the originality of the objective facts, methods/procedures or ideas.

10) Cases upholding the copyrightability of applied art

Nagasaki District Court (Sasebo Branch) judgment of February 7, 1973, on the Hakata Doll case (Mutaireishu, Vol. 5, No. 1, p. 18))

In this case, the doll entitled Akatombo (red dragonfly) can be deemed to be a production in which sentiments are expressed in a creative way, in consideration of its figure, facial expression, the design of clothes and colors, and it has artistic quality that is regarded as the value of artistic craftsmanship … Accordingly, the doll in question should be protected as a work of crafts of artistic value as specified in the Copyright Act.

Kobe District Court (Himeji Branch) judgment of July 9, 1979, on the Buddhist Altar Sculpture case (Mutaireishu, Vol. 11, No. 2, p. 371)

It is appropriate to consider the articles that are mainly intended for the artistic appreciation of the aesthetic representation expressed there as comparable to fine arts even if they are used as utilitarian goods and to confer copyrights on them.

11) Cases rejecting the copyrightability of items of applied arts

Kyoto District Court judgment of June 15, 1989, on the Saga Nishiki Double-Woven Kimono Sash case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1327, p. 123)

Although aesthetic creations of which the primary purpose is to be used as a pattern in utilitarian goods, such as the design of kimono sashes, are considered to be protected as artistic works under the Copyright Act, only if they also have the nature of fine art, it is considered that the decision of whether or not the creations have the nature of fine art should be made from the standpoint of whether, when viewed objectively, the object could become an object of aesthetic appreciation as a completed art work aside from its intrinsic utilitarian function, not from the standpoint of whether the object was created for the exclusive purpose of aesthetic expression as the subjective intention of the creator.

Tokyo High Court judgment of December 17, 1991, on the Wood Grain Decorative Paper case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1418, p. 120)

Items of applied art that were produced exclusively for such use as the pattern in utilitarian goods could be considered to fall within the category of artistic works under the Copyright Act if they have high artistic quality (in other words, a high level of creative expression of thoughts or sentiments) and to affirm its nature as fine art would conform to conventional wisdom.

12) Case rejecting the copyrightability of typefaces and font designs (Supreme Court judgment of September 7, 2000, on the Gona U Print Typeface case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1730, p. 123))

For print typefaces to fall within the definition of works, they must have ingeniousness such as distinctive characteristics compared with existing typefaces, and also must have aesthetic properties that could serve, in themselves, as objects of artistic appreciation… Since typefaces are required to fulfill the function of letters, which is to communicate information, there are inevitably some limitations on their forms. If typefaces were generally protected by copyright, … copyright would result from numerous typefaces that are only slightly different. This would result in complex relationships among rights and would cause chaos.

13) Case ruling that architectural works refer to buildings of great artistry (Osaka District Court judgment of October 30, 2003, on the Model House case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1861, p. 111))

Ordinary, garden-variety buildings should not be considered to fall within the category of architectural works, which are protected by the Copyright Act. … It is appropriate to consider that general houses are seen as architectural works as specified in Article 10, Paragraph 1, Item No. 5 if they have artistic or aesthetic quality that would cause ordinary individuals to perceive cultural spirituality, such as thoughts or sentiments of architects or designers, beyond the aesthetic factors usually added to general houses, in other words, if they have originality that could be described as so-called architectural art.

14) Case rejecting the originality of woodblock print photographs (Tokyo District Court judgment of November 30, 1998, on the Woodblock Print Photograph case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1679, p. 153))

When photographs were taken to replicate existing planar woodblock prints, there was no other choice but to take them from the front, and the technical considerations recognized were made in order to reproduce the original prints as faithfully as possible, not to add something independently. The photographs taken in this way cannot be considered to be a production in which thoughts or sentiments are expressed in a creative way.

15) Case holding that originality is rejected when program descriptions are mundane (Tokyo District Court of January 31, 2003, on the Drafting Program case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1820, p. 127))

Computer programs, by nature, use a limited number of symbols for expression and are written in strict language systems. Accordingly, efforts to have computers operate effectively and efficiently often cause similarities in description of programs due to the limited choice of combinations of instructions… The Copyright Act protects specific expressions of programs and does not protect functions of programs or ideas from which programs are created. If specific descriptions of programs with particular functions are mundane and if the descriptions are to be protected, that would ultimately protect the functions and ideas per se and allow the copyright owners to keep them to themselves. Accordingly, if program descriptions, which are a combination of instructions to computers, are mundane, they should be considered to lack the programmer’s individuality and thus lack originality.

16) Case holding that the copyright in derivative works extends only to newly added original parts (Supreme Court judgment of July 17, 1997, on the Popeye Necktie case (Minshu, Vol. 51, No. 6, p. 2714))

It is appropriate to consider that copyright in a derivative work extends only to the newly added original part and does not cover the parts that are the same as, and share the same substance as the pre-existing work. A derivative work receives copyright protection as a work that is independent of and separate from the preexisting work because new original elements have been added to the preexisting work, and the parts in the derivative work that are the same as in the preexisting work contain no new original elements and lack justification for protection as a separate work.

17) Case holding that the copyright protection of compilations is not intended for the abstract selection or arrangement methods (Tokyo District Court judgment of March 23, 2000, on the Color Chart case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1717, p. 140))

Article 12, Paragraph 1 of the Copyright Act provides that compilations that are original by reason of the selection or arrangement of their contents shall be protected as works (compilations). This is intended to protect specific expression which is the fruit of the intellectual creative activity of selecting or arranging pre-existing material, not to protect the abstract selection or arrangement methods apart from the pre-existing material and the compilations that are the results of selecting or arranging the material. What are the preexisting materials that have made up the compilation in question should be judged comprehensively based on the usage of the compilation, actual forms of expression used in the compilation, etc.

II. Judicial precedents concerning authors

1) Case ruling that persons who are not considered to have expressed their thoughts or sentiments in a creative way do not qualify as authors (Tokyo District Court judgment of October 29, 1998, on the SMAP Interview Article case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1658, p. 166))

A person who actually engaged in the creative activity involved in the work in question shall qualify as the author, and the individuals who are not considered to have expressed their thoughts or sentiments in a creative way in the creation of the work based on the degrees and forms of their involvement, such as persons who did no more than provide ideas or materials and persons who played no more than an auxiliary role in the creation of the same, do not qualify as authors… When literary works expressed as documents are concerned, persons who actually made creative contribution to the documents and engaged in creative expression as documents should qualify as the authors.

2) Case holding that the instructions for the creation or correction of illustrations are not subject to copyright protection (Tokyo District Court judgment of March 31, 1997, on the Home Care Anyone Can Do case (Hanrei Jiho, No. 1606, p. 118))

Even if the plaintiff gave the instructions as to which parts of the reference literature should be referenced …, the instructions constituted no more than a specific request for creating illustrations or cartoons, and since Ms. Matsuko Koda (an employee of the defendant company) actually expressed them in concrete terms through the creation of illustrations or cartoons, she, not the plaintiff, is the author… Even if the plaintiff placed the order and gave instructions to partially correct the illustrations created by Koda, … the order and instructions can be seen as part of the specific request or order for creating cartoons and cannot be considered to be subject to copyright protection for illustrations or cartoons.

3) Case affirming the initiative of a juridical person when a work is created by its employee in the course of his/her duties according to the juridical person’s business plan or an agreement concluded between the juridical person and a third party without the juridical person assigning the employee to the creation of the work if it is anticipated and expected that the work will naturally be created by the employee in the course of his/her duties (Intellectual Property High Court judgment of August 4, 2010, on the Collaborative Research Report case (Supreme Court website))

When an individual who has an employment relationship with a juridical person or other employer created a work in the course of his/her duties according to the business plan of the employer or an agreement concluded between the employer and a third party, it should be considered that the requirement (for works made for hire) that the work was created on the employer’s initiative was met without the employer assigning the employee to the creation of the work or giving consent to the same if it was anticipated and expected that the work would naturally be created by the employee in the course of his/her duties.

Note: This is a case holding that the work-for-hire requirements have been met concerning the report drawn up by a faculty member who served as the representative of a collaborative research program implemented based on an agreement concluded between a city government and the university where the faculty member works.

4) Case affirming the initiative of a juridical person or other employer regarding a work created by its employee in the course of his/her duties without the employer assigning the employee to the creation of the work and holding that a work to which a juridical person’s name should be appended supposing it were made public is equivalent to a work to be made public by a juridical person or other employer as a work under its own name (Intellectual Property High Court judgment of December 26, 2006, on the National Space Development Agency of Japan case (Supreme Court website))

In regard to the requirement (for works made for hire) that the work was created on the initiative of a juridical person or other employer, no one disputes that the work was created on the employer’s initiative when the employer planned and envisaged the creation of the work and assigned a person engaged in its business to the creation of the work, or when a person engaged in the employer’s business created the work with the employer’s consent. Furthermore, if a person who had an employment relationship with the employer created a work in the course of his/her duties according to the employer’s business plan, it is appropriate to consider that the requirement that the work was created on the employer’s initiative was met without the employer assigning the employee to the creation of the work or giving consent to the same if it was anticipated and expected that the work would naturally be created by the employee in the course of his/her duties. The requirement that a work was created in the course of an employee’s duties should be considered to include the work created by a person engaged in his/her employer’s work with a direct order to create the work and also include the act in which the program would naturally be created by the person engaged in the employer’s work in the course of his/her duties. It is appropriate to consider that the requirement that the employer make the work public under its own name is also met for works for which there is no plan to make them public but which should be made public under the employer’s name supposing they were made public.